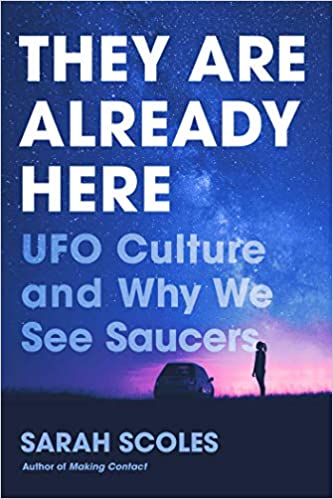

I defied flying objects Journalist Sarah Scoles’s ‘They Are Already Here’ explores people’s obsession with discovering what else may be out there. Let’s get this out of the way: They Are Already Here: UFO Culture and Why We See Saucers definitely sounds like a certain kind of book, and in some ways it lives up to its billing. Yes, this book is a peek into the obsessive world of people who have seen unidentified objects in the sky—or who really, really want to someday. If you thought that UFO-curious guy from Blink-182 and those Navy pilots who spotted strange objects on their radars were onto something, this one is definitely for you. Ditto for fans of The X-Files, Independence Day, or Men in Black II.

But in the hands of Sarah Scoles

It turns out that the UFO community is vast and not entirely composed of truthers who are convinced that extraterrestrial beings are attempting to contact us. For the first third of the book, Scoles digs into conspiracies surrounding national UFO news, like military sightings of mysterious flying objects. It’s a little in the weeds for readers who aren’t obsessed, but it’s a helpful primer on the fascinating individuals and organizations who form a loose subculture of theorists and seekers: some have convoluted ties to government officials, some have a deep distrust of the government, and others just have deep pockets. As Scoles points out while discussing the UFO-seeking businessman Robert Bigelow, wealth “seemed to shield him from stigma…. When you have a high enough bank balance, and have succeeded in being a CEO rather than a guy ranting on the street, people mostly shrug and write colorful magazine profiles of you.” But some of the most interesting parts of the book include Scoles’s attempts to understand people who aren’t eccentric billionaires and haveseen something they can’t explain.

Scoles often writes about desert landscapes in a way that makes you think, Of course people see things here! She explores the isolated locations of extraterrestrial lore: Roswell, New Mexico; the Bureau of Land Management territory around Area 51; the Arecibo and Sunspot observatories in Puerto Rico and New Mexico, respectively; and the UFO Watchtower, in Colorado’s San Luis Valley. (For some reason, the extraterrestrials spotted by humans seem to have a strong preference for the less populated landscapes that we earthlings also like to escape to.) “This plain has menacing topography,” Scoles writes from near Area 51 and Yucca Mountain, Nevada, where the government has considered dumping nuclear waste for decades. “Here, [mountains] are sharp mounds of semi-permanent dirt, hydrodynamically eroded into caverns and cones, rising from nothing.”

During the reporting of that section, Scoles and her friends have a spooky encounter while trying to find a place to camp: they see lights that seem to linger exactly where they are and that blink away at menacing times. (It’s less scary for its extraterrestrial implications than for the fact that it could be a car idling suspiciously near a group of three women off an isolated road, as Scoles’s friend points out.) They eventually fall asleep and wake up the next day without further incident, but they begin to see how simply being out there in a remote and arid landscape at night might give people a heightened sense of uncertainty. The desert can imbue anything—an animal’s footsteps around a tent, a light in the sky that doesn’t quite behave like a star or an airplane—with mystery or dread. Encountering a UFO, it seems, can feel just the same as encountering any kind of unidentified object under the right circumstances.

Of course, not all UFO encounters are scary. In fact, what stuck with me most from the book were meditations from Scoles’s interviewees about their feelings of awe and discovery in the presence of something that might have been extraterrestrial in nature. Scoles doesn’t aim to convert skeptics—she is one herself—but instead tries to help us understand the mindset of UFO believers. What would happen to you if you thought you’d seen something that a lot of other people don’t believe in? How would you describe it? What would it mean to you? How would you feel if not that many other people could understand what it was like? Scoles recalls that historian Greg Eghigian once told her that “what grabs people is not that UFOs show up. It’s that they go away.

“You can spend your life searching, seeking,” he said.

The outdoor experiences we chase, I think, provoke feelings in us that are not so different from the ones the UFO community experiences, too. Anyone who’s camped under the Milky Way or headed for a summit at dawn can find resonance there. So much of the thrill of getting outside is how fleeting, overwhelming, and deeply humbling it can all be—how small a single person can feel compared to the entirety of the universe, and how hard that is to explain. We’ve all been to a vista that just didn’t look the same when we tried to photograph it, or felt elated recognition just after completing some superhuman sufferfest. Maybe we’ve even seen something while stargazing that we can’t totally explain.

Scoles deftly gets to the heart of what we feel when we think we’ve connected with something sent from the greater universe: whatever’s out there, maybe it wants to know us and be known, and the experience of discovery makes us special. “A very small, very arrogant part of me wants to believe, though I know it isn’t true, that this too-perfect celestial show is for us,” she writes.

Great book hope you enjoy during our Quarantine during the Coronavirus Pandemic. With your tinfoil hat on be sure and pop some popcorn too!

Love and Peace,

Thank You,

Nancy Thames